New dating for White Sands footprints confirms controversial theory

Results are consistent with two earlier studies dating the footprints to between 22,000 and 24,000 years ago.

Credit:

US Geological Service/Public domain

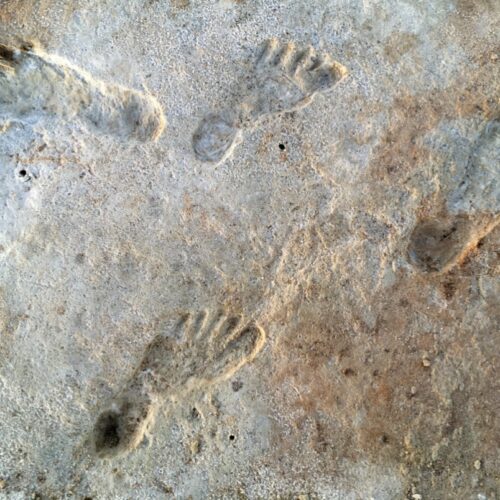

The 2009 discovery of footprints (human and animal) left behind in layers of clay and silt at New Mexico’s White Sands National Park sparked a contentious debate about when, exactly, human cultures first developed in North America. Until about a decade ago, it seemed as if the first Americans arrived near the end of the last Ice Age and were part of the Clovis culture, named for the distinctive projectile points they left behind near what’s now Clovis, New Mexico. But various dating methods indicated the White Sands footprints are 10,000 years older. Now there is a fresh independent analysis that agrees with those earlier findings, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances.

As previously reported, earlier archaeological evidence had suggested the Clovis people made their way southward through a corridor that opened up in the middle of the ice sheets between 13,000 and 16,000 years ago. Subsequent archaeological evidence—such as a 14,500-year-old site in Florida and stone tools dating to 16,000 years ago in western Idaho—suggested that the Clovis people were actually not the first to arrive. It also made it look much more likely that the first Americans had skirted the edge of the ice sheets along the Pacific Coast.

The White Sands footprints further muddled the narrative. In 2019, Bournemouth University archaeologist Matthew Bennett and his colleagues excavated the White Sands area and found a total of 61 human footprints east of an area called Alkali Flat, which was once the bed and shoreline of an ancient lake. Over time, as the lake’s edge expanded and contracted with shifts in climate, it left behind distinct layers of clay, silt, and sand. Seven of those layers, in the area Bennett and his colleagues excavated, held human tracks along with those of long-lost megafauna.

Some of the sediment layers contained the remains of ancient grass seeds mixed with the sediment. Bennett and his colleagues radiocarbon-dated seeds from the layer just below the oldest footprints and the layer just above the most recent ones. According to those 2021 results, the oldest footprints were made sometime after 23,000 years ago; the most recent ones were made sometime before 21,000 years ago.

At that time, the northern half of the continent was several kilometers below massive sheets of ice. The existence of 23,000-year-old footprints could only mean that people were already living in what’s now New Mexico before the ice sheets sealed off the southern half of the continent from the rest of the world for the next few thousand years.

Ancient human footprints found in situ at White Sands National Park in New Mexico.

Credit:

Jeffrey S. Pigati et al., 2023

Other researchers were skeptical of those results, pointing out that the aquatic plants (Ruppia cirrhosa) analyzed were prone to absorbing the ancient carbon in groundwater, which could have skewed the findings and made the footprints seem older than they actually were. And the pollen samples weren’t taken from the same sediment layers as the footprints.

So the same team followed up by radiocarbon-dating pollen sampled from the same layers as some of the footprints—those that weren’t too thin for sampling. This pollen came from pine, spruce, and fir trees, i.e., terrestrial plants, thereby addressing the issue of groundwater carbon seeping into samples. They also analyzed quartz grains taken from clay just above the lowest layer of footprints using a different method, optically stimulated luminescence dating. They published those findings in 2023, which agreed with their earlier estimate.

More evidence in the mud

Still, the skeptics remained unconvinced, suggesting that the 2023 results were maximum ages, not estimates of true age. So, co-author Vance Holliday of the University of Arizona (who also co-authored the 2021 paper) and colleagues decided to radiocarbon-date ancient lake bed and wetlands mud that can be directly traced to the alluvium layers in which the footprints are preserved. These results peg the dates to between 20,700 and 22,400 years ago, once again consistent with the earlier findings.

The Alkali Flat east escarpment: (a) the view east; (b) southeast view.

Credit:

Vance T. Halliday

Per Holliday, that makes for a grand total of 55 radiocarbon results in support of the earlier dates across the three studies. “It’s a remarkably consistent record,” said Holliday. “You get to the point where it’s really hard to explain all this away. It would be serendipity in the extreme to have all these dates giving you a consistent picture that’s in error. I really had no doubt from the outset because the dating we had was already consistent. We have direct data from the field—and a lot of it now.”

There’s yet another criticism of this earlier timeline that even Holliday admits is perfectly valid: To date, archaeologists haven’t discovered any artifacts or evidence of settlements that the humans who made those footprints should have left behind. Holliday speculates that at least some of the footprints were made in what were once trackways that took mere seconds to traverse. So it’s unlikely these hunter-gatherers would have left behind such traces. “These people live by their artifacts, and they were far away from where they can get replacement material. They’re not just randomly dropping artifacts,” Holliday said. “It’s not logical to me that you’re going to see a debris field.”

Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv4951 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.