New body size database for marine animals is a “library of life”

Marine Organizational Body Size (MOBS) database fills a crucial gap in understanding ocean biodiversity.

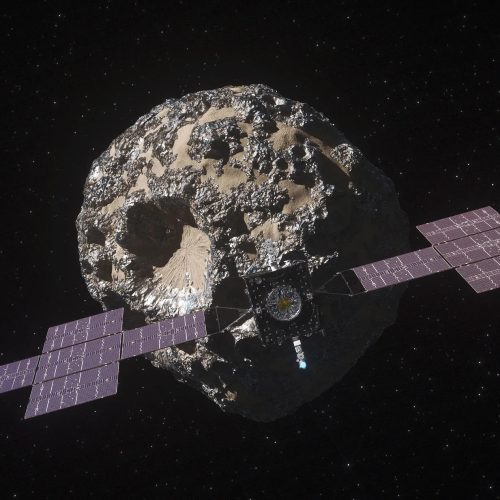

Craig McClain photographing a whale shark off the coast of Cancun, Mexico, to collect body size data.

Credit:

Alistair Dove

Legend has it that physicist Ernest Rutherford once dismissed all sciences other than physics as mere “stamp collecting.” (Whether he actually said it is a matter of some debate.) But we now live in the information age, and scientists have found tremendous value in amassing giant databases of information for large-scale analysis, enabling them to explore different kinds of questions.

The latest addition is the Marine Organizational Body Size (MOBS) database, an open-access resource that—as its name implies—has collected body size data for more than 85,000 marine animal species and counting, ranging from microscopic creatures like zooplankton to the largest whales. MOBS is already enabling new research on the ocean’s biodiversity and global ecosystem, according to a paper published in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography. The database is now available though GitHub and currently covers 40 percent of all described marine animal species, with a goal of achieving 75 percent coverage.

“We’ve really lacked that broader persecutive for a lot of ocean life,” marine ecologist Craig McClain of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette told Ars. McClain is the lead creator of MOBS. “We know about evolution and ecology for mammals and birds especially, and to a lesser extent reptiles and amphibians. We just haven’t had these big collated body size data sets for the marine groups, especially the invertebrates.” The MOBS project is basically constructing a “library of [marine] life.”

This in turn paves the way for research on macroecology and macroevolution for marine animals. As McClain likes to say, “Body size isn’t just a number; it’s a key to how life works,” because that simple trait is related to “how a species moves, eats, survives, and evolves. What jellyfish do and their ecology is so much different than for a mammal that it makes you wonder how universal some of the [widely accepted] ‘rules’ really are.”

The ocean runs on size

McClain officially launched MOBS as a passion project while on sabbatical in 2022 but he had been informally collecting data on body size for various marine groups for several years before that. So he had a small set of data already to kick off the project, incorporating it all into a single large database with a consistent set format and style.

Craig McClain holding a giant isopod (Bathynomus giganteus), one of the deep sea’s most iconic crustaceans

Credit:

Craig McClain

“One of the things that had prevented me from doing this before was the taxonomy issue,” said McClain. “Say you wanted to get the body size for all [species] of octopuses. That was not something that was very well known unless some taxonomist happened to publish [that data]. And that data was likely not up-to-date because new species are [constantly] being described.”

However, in the last five to ten years, the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) was established with the objective of cataloging all marine life, with taxonomy experts assigned to specific groups to determine valid new species, which are then added to the data set with a specific numerical code. McClain tied his own dataset to that same code, making it quite easy to update MOBS as new species are added to WoRMS. McClain and his team were also able to gather body size data from various museum collections.

The MOBS database focuses on body length (a linear measurement) as opposed to body mass. “Almost every taxonomic description of a new species has some sort of linear measurement,” said McClain. “For most organisms, it’s a length, maybe a width, and if you’re really lucky you might get a height. It’s very rare for anything to be weighed unless it’s an objective of the study. So that data simply doesn’t exist.”

While all mammals generally have similar density, “If you compare the density of a sea slug, a nudibranch, versus a jellyfish, even though they have the same masses, their carbon contents are much different,” he said. “And a one-meter worm that’s a cylinder and a one-meter sea urchin that’s a sphere are fundamentally different weights and different kinds of organisms.” One solution for the latter is to convert to volume to account for shape differences. Length-to-weight ratios can also differ substantially for different marine animal groups. That’s why McClain hopes to compile a separate database for length-to-weight conversions.

While body size might seem to be a relatively easy measurement to take, compared to something physiological like metabolic rate, when it comes to marine animals there can be unique challenges. McClain recalled working on a project to measure the length of whale sharks in the wild. “You can’t just swim up and extend a tape measure down the length of a whale shark,” he said.

The solution was admittedly convoluted, but it worked. “We would swim up to the shark, shoot a couple of laser dots on their side at known widths, and take pictures. We knew that the distance between their last gill and the dorsal fin scaled with total body length, so that’s how we figured it out.” By contrast, measuring the lengths of submillimeter organisms has typically involved taking multiple images under a microscope and conducting image analysis.

Scientists are already using MOBS to study things like whether the size-related patterns in descriptions of species in biodiversity databases might reflect longstanding biases, for example. But it also provides McClain and his team with a viable research focus at a time when federal funding for scientific research is facing an existential crisis.

“The other work I do, deep sea research, is very expensive and requires grant funding,” said McClain. “The great thing about this project is that it only really requires me and a laptop and some other people and their laptops. It may be over the next few years, while there’s no funding to do any other field or lab science, that this may be our main focus. At the end of the day, [MOBS] is going to require lots of people approaching this from a lot of different ways to get great coverage across all these different groups.”

DOI: Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2025. 10.1111/geb.70062 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.